By: David Lombino

By: David LombinoThe Litchfield County Times, April 11, 2003

WASHINGTON-By its nature, biography is an imperfect medium as it attempts to stitch together events both monumental and seemingly inconsequential to convey the essence of an engaging character. Never is the scope broad enough to capture something as large as a life, nor are the sources close enough to reveal inner truths.

Still, in an upcoming three-day exhibition at Bryan Memorial Town Hall, Dimitri Rimsky will provide an opportunity for the world to see his father in a form that attempts to be as complete, honest and accurate as possible.

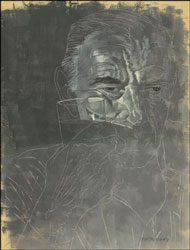

Almost every remaining artwork by Feodor Rimsky will be shown-more than 500 works in all, in addition to binders filled with pencil and pen sketches, miniature studies of forms, even doodles on napkins. Collectively, and most importantly for his son, the show will present the opportunity for the audience to witness the birth, struggle and the realization of an artist's idea.

"My father in his lifetime never mounted a show like this," said Mr. Rimsky, who is a Web designer and freelance remodeling contractor. "Most artists would never mount a show like this, and I am not so sure that's a good thing," Mr Rimsky said. "It leaves their audiences ignorant of the effort. We have this illusion that artists stand in front of a canvas and paint something. They don't. It's not 9 to 5. In general, artists take an idea, work on it for a lifetime. Sometimes, they finish it."

The painter's classical European style and traditional subject matter was hardly in vogue during the 1950s, when the American art scene was driven by Abstract Expressionism. "He was not successful as an artist in this country, really. That's not to say he wasn't a successful artist," his son said.

The elder Mr. Rimsky insisted on live sittings with models for portraits. He was unafraid of experimenting with different techniques-holding a commercial drawing up against a private work, the two are hardly recognizable as being born from the same easel. He made life-sized watercolors, huge concept paintings of crucifixions, dozens of portraits, and complete flights of fantasy.

"Who is this artist?" asked Mr. Rimsky, who admits that the exhibition is at least partly an exercise to resolve that question. "The intent is to show the community what this artist who lived among them did. He lived here for 36 years, half of his life, and I'd say probably not more than a dozen people know what his work is about."

In the converted carriage house where he grew up and now lives, Mr. Rimsky enthusiastically traces the development of one his father's works from thumbnail sketch to finished product. The artist adjusted his vision and technique to try to reproduce something from his imagination, battling constantly with the imperfection of what appears on the surface. One recurring subject that seems to represent a lover's embrace is actually a scene from a street corner in Berlin just after World War I, where the artist witnessed a pimp stabbing a prostitute.

"The audience will be able to see something very unusual. They will see the progression or development of an idea," Mr. Rimsky explained. "The rethinking of a concept over and over again. They will be able to see that there is more to a painting than the final product. We think of art as the thing we see on the wall and that's like seeing a child as an orphan. In fact, it is not an orphan. It comes from something. It comes out of the life of the artist."

Feodor Konstantin Rimsky lived through a turbulent 43 years of European history, before escaping Vichy, France for the United States on a vessel leaving Lisbon in 1941. Born in Tula, a town south of Moscow in 1898, he was sent to the "Gray Cloister" boarding school in Berlin at the age of 12. When World War I broke out, and his motherland became an enemy of the Germans, he was put to work in a steel factory.

When the Russians pulled out of the war to fight the internal battle of the Russian Revolution, Feodor Rimsky was forever deprived of his homeland. His family was staunchly anti-communist-his father fought for the White Russians-so he stayed in Germany as a student and attended the University of Berlin in the 1920s.

While at university, he participated in the "free corps," a group of students who fought against the German-communist uprising, many of whom were students who sat next to him in class. He slept with a pistol and hand grenades, and he engaged communists who would physically stop German workers from trying to go to work.

In the wild 20s in Berlin, Mr. Rimsky established himself successfully in the business world, and he held some patents that dealt with processing metal. He used his monetary success as a springboard into the art world, and his early art career consisted of sketches and drawings for German book covers, publications, playbills for the Brecht-Reinhardt theaters.

At a Valentine's Day masquerade ball at the U.S. embassy in Berlin, Feodor met Pitra, an American woman who would become his wife. Increasingly uncomfortable with the chaos of Weimar Germany and the rise of the Nazi party, the couple moved to Paris in the early 1930s, where Mr. Rimsky took over Whistler's studio and they took part in the contagious cafe culture of the Lost Generation. When that enlightened movement collapsed under Nazi aggression, Mr. Rimsky's brother-in-law, a French secret service agent, got the couple on one of the last trains to Vichy, France. They married, which represented his third marriage, and left for the United States. When they returned seven years later to collect their belongings, nearly all of Mr. Rimsky's artwork was missing.

Stateside, they settled into a studio-home in the West Village in Manhattan, where Mr. Rimsky engaged in commercial and illustrative work, most notably the book covers for Fulton Oursler's books, "The Greatest Story Ever Told" and "The Greatest Book Ever Written." The ethereal and sensitive Christ on the cover of "The Greatest Story Ever Told" was inspired from portraits of Pitra.

The couple moved part-time to Washington in 1950, locating the cultural oasis through a friend who taught at The Gunnery private school. During the 50s, Feodor Rimsky became involved in the artistic community in Washington, as one of the founders of the Washington Art Association in 1952, and a participant in the Wykeham festivals, painting the 30-foot mural of the mid-1800s railroad Depot in the Litchfield Bancorp building, and constructing sets and drafting designs for the talented amateur theatrical group, Dramalites.

"I think in Washington there were a lot of paradoxes. I think as a European and as a Russian, throughout the 1950s he was dealing with discomfort from McCarthyism and a great deal of suspicion. I think, as a European, he had always felt slightly like a fish out of water here," said Mr. Rimsky, adding, "But the artistic community around here was extremely vital. There were and still are a culture of artists, writers and musicians. This is not a sleepy little town beneath the surface."

The younger Mr. Rimsky now looks to engage that community again, and the time and effort that went into putting together the exhibit is impressive. All the work has been cataloged, priced, sized, in some cases mounted, matted, cleaned and repaired-an exercise that has taken Mr. Rimsky three months.

Clearly he believes his father's work is extraordinary, and admittedly part of his motivation for having the exhibition is to get some public recognition and establish a reputation. But since his father's death in 1976, Mr. Rimsky has battled with a significant challenge, and one he believes is not unique, about what to do with his father's massive body of work.

"Furniture is easy to sell. Clothes you give to Goodwill. If it's art, it has a life in it still. You can't burn it. You can't throw out the least piece of it. Your sense of attachment to that part of a deceased person-it's difficult to come to terms with. Every living orphan of an artist is faced with that dilemma," he explained. "If you're not a Calder, what do you do? What if grandma painted every Sunday in the garden? You have 100s of paintings of lilies. What do you do?"

Mr. Rimsky feels guilty for sitting on his father's work for more than 26 years, immobilized by emotion and the size and scale of the project. The carriage house where he lives is a shrine to his father's work, and nearly every inch of surface area on the second floor studio is wallpapered with paintings and sketches. The closets are jammed with giant rolled murals.

"It's a paradox. I am surrounded by the life of my father, and in that sense death has no dominion. On the other hand, I am surrounded by a dead father. Where there is consolation, there is also constant confrontation," he reasoned. "On a personal level, the exhibition is a coming of age for myself as the son of an artist. It's facing a responsibility to the art and to the parent."

Mr. Rimsky plans to use any profits from the exhibition to start a foundation to help families of deceased artists manage the legacy they have been left. He envisions an organization that would assist with online placement, distribution, non-biased evaluation and managing grief. He hopes this exhibit will also serve as an example. "No creative life should go unrecognized," he said.

"Feodor K. Rimsky: A Lifetime of Art, 1898-1976" will show at Bryan Memorial Town Hall in Washington Depot on April 25, 26 and 27. Works are available for purchase from $5 to more than $10,000. A preview party with refreshments and hors d'oeuvres provided by the Pantry is to be held April 25, from 5 p.m. to 8 p.m. The cost is $25 and reservations are suggested. On Saturday, the exhibition opens at 10 a.m. and there will be talking tours conducted by Dimitri Rimsky at 5 p.m. and 7 p.m. On Sunday, the exhibition is open from noon to 8 p.m. and a silent auction will close at 7 p.m. For more information, Mr. Rimsky may be reached at 860-868-9669, via email at rimsky3@hotmail.com or on the artist's Web site, www.feodorrimsky.com.